Once upon a time, it was Bolivia’s second-largest lake. Today, it has all but vanished. New satellite images have confirmed this. The disappearance of Lake Poopó has dramatic consequences for wildlife – and people.

It’s a surreal image: fishing boats left behind on dead, dried ground, being whipped around by heavy winds. On this 3,000-square-kilometer (1,160-square-mile) desert of cracked earth once stretched Lake Poopó, Bolivia’s second-largest lake after Titicaca.

Lake Poopó was once home to numerous animal species, in addition to providing sustenance for local people. Today, the lake is all but gone – satellite images recently confirmed this. All that’s left are three swampy areas, in former depths of the lake.

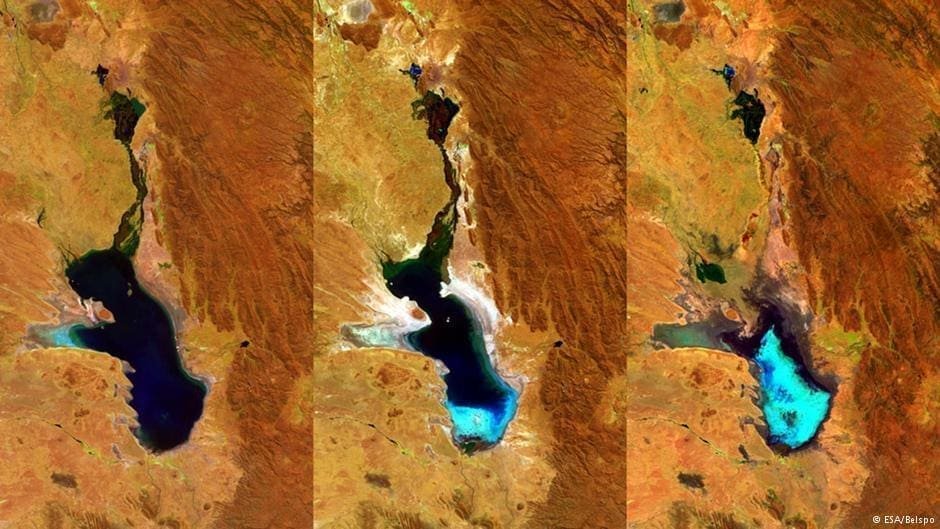

Bolivian media reported Tuesday (09.02.2016) on how water in the Poopó had gradually evaporated. Images from the European Space Agency’s Proba-V Earth-monitoring satellite from April 2014, July 2015 and January 2016 have proven that the lake, in Bolivia’s southwest, is practically gone.

Natural disaster – caused by humans?

Zenon Pizarro, parliamentary president in the neighboring city of Oruro, decried the situation. “This is a natural disaster with devastating consequences for the region around Oruro, and for all of Bolivia,” Pizarro said.

The city had already declared a state of emergency over the drying lake in December, but Bolivian President Evo Morales had placated fears by saying this was a normal cycle for the lake, which becomes dryer toward the end of the year before refilling.

What this does not take into account is how rainfall has also steadily decreased in the region over the years.

“This is a climate disaster,” said Raúl Pérez Albrecht, head of the Latin American Environmental Network. “Temperatures in the region have increased nearly 2 degrees [Celsius] over the past three decades – rain is ever more seldom,” Albrecht continued.

Another major factor contributing to the lake’s decline is diversion of water from the river that feeds the lake, for agriculture or for the many silver and tin mines in the region.

Gradual shrinkage

Already once in the 1980s, the lake dried out completely. The water came back that time, although the lake never again reached its original size. It has shrunk from year to year, Albrecht said.

Following the Desaguadero River toward the dry lake, the effects can be felt directly. At the town of Eukaliptus, water is diverted from the river for a silver mine and into fields for watering crops.

“The water is gone. The fields are drying out. We are very worried about this,” said fisherman Juan Iquina. Holding his net at one of the diversion canals, Iquina – like many other fishermen – has fading hopes for a good catch.

Fleeing from the drought

Further away from the dried-out lake, near the city of Oruro, a small lagoon holds a little water – and a lot of trash. Thousands of flamingos wade through the stinking sludge.

The flamingos search for edible brine shrimp and blue-green algae among empty plastic bottles, plastic bags and stagnant puddles. They’ve fled from the drought, and the dried-up Lake Poopó – but it’s not clear whether what they find here will sustain them.

The people, as well, are fleeing – only 350 families still live at Lake Poopó. While in the past they were able to fish in the lake and irrigate their quinoa fields, now they fight to survive each day.

“The single source of income we had was from selling fish,” said Don Silverio, an older fisherman. His people, the Uru Indians, lived off the lake for untold ages.

“With the lake’s disappearance, we’ve lost our livelihood. We have no income anymore,” Silverio said.

The Uru village, with about 90 families, still has access to a well, and survives off rice and potatoes provided by the state.

But they, too, are likely to leave their home in search of anew livelihood.

Source: DW